by Nomad

If a picture is worth a thousand words, what is the story behind this photograph? The young woman's name is Dorothy Counts.

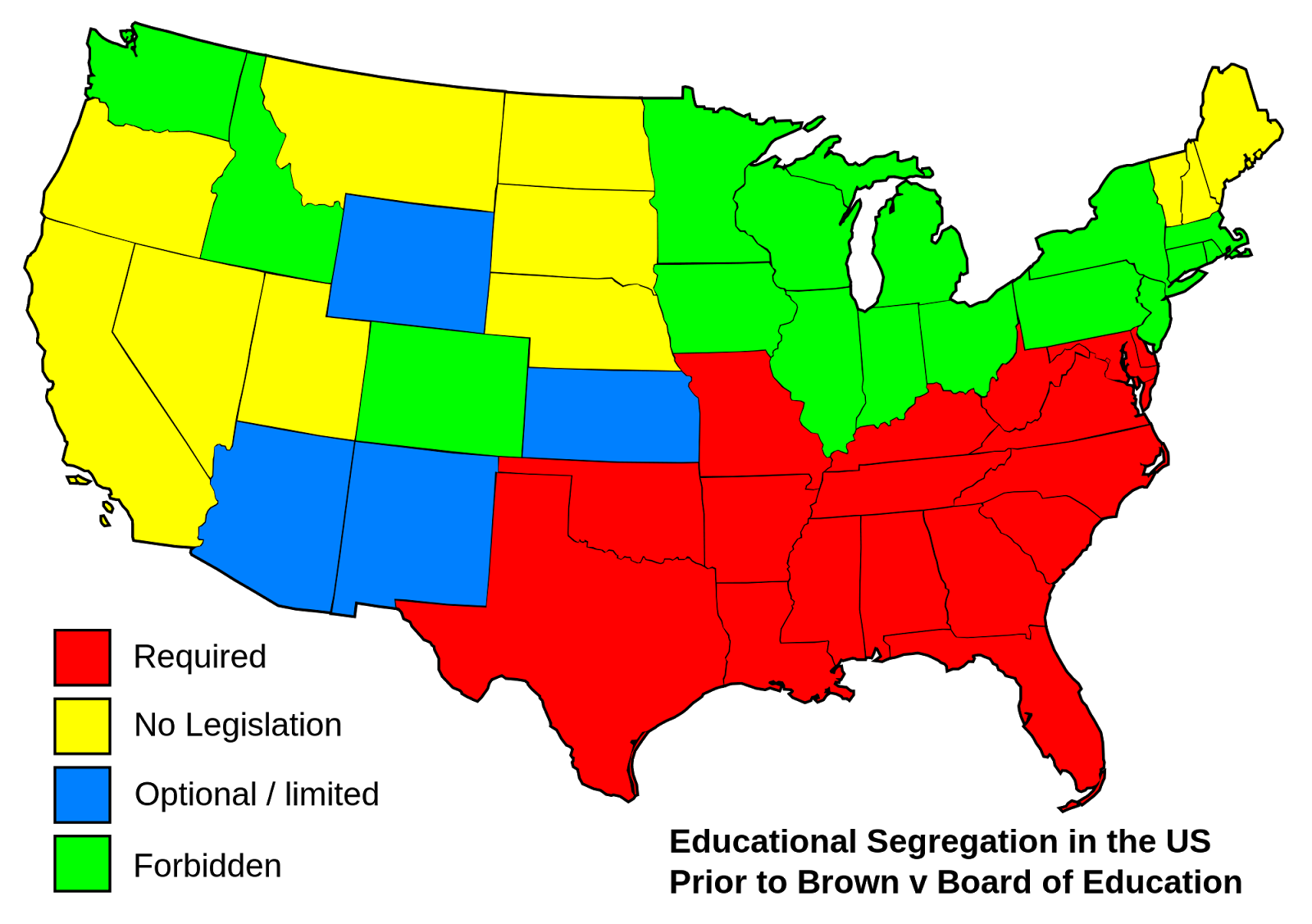

We tend to think of the 1960s as the Era of the Social Movement but in fact, the great sweeps of reform began a decade earlier. The movement. it's true, reached its zenith during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. However, the impetus for social change began as a result of a constitutional challenge mostly that eventually made its way to the high court.

It was the culmination of a campaign by The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and its legal offspring, the Legal Defense and Educational Fund, against the doctrine of “separate but equal.”

This constitutionally approved doctrine was seen as a kind of loophole that justified and permitted state-sponsored racial segregation so long as the services, facilities, public accommodations, housing, medical care, education, employment, and transportation be separated along racial lines,were of equal quality

The Showdown

This issue had been simmering for a long time. The South was adamant that its white children and its black children didn't need to be taught in the same schools. In the South, the idea of separation of the races was deeply embedded in the culture.

Segregated schools were, they argued, following the long-held policy of a separate but equal education for whites and blacks. The problem was that black schools simply were not equal. no matter how much state officials claimed. All black schools, as Professor Leonard A. Slade Jr. writes,

"enjoyed less funding than the all-white schools, meaning that teachers earned lower salaries and that money for lab equipment and other facilities was scarce."

Without an equal education, black students could not expect an equal opportunity. Nevertheless, any talk of mixing the races was for some- especially in the South- was offensive. A call to arms against the “mongrelization” of the races.

For instance, in 1951, the Governor of South Carolina James F. Byrnes warned that, if the court declared against segregation, his state would be forced reluctantly to "pull out of the public school system."

Similar tactics of holding the public hostage to political principle have been used today when it came to affordable health care.

At the end of the day, such threats had no impact on the legal debate.

The Court Rules

Three years after Byrnes' threat, on May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court in its unanimous ruling in Brown v. Board of Education outlawed segregation in public schools.

Chief Justice Earl Warren speaking for the court read the ruling:

We come then to the question presented: Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does...

The justices found that the Segregation of white and black children in public schools had a detrimental effect upon the African American children. That impact, they added, was greater when it had "the sanction of the law."

We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

It was a courageous decision but few at the time knew what the effects of the ruling might be. It was already clear even then that many in the South would simply not stand for it.

Governor Herman Talmadge insisted that Georgians "will fight for their right under the U.S. and Georgia constitutions to manage their own affairs," adding that the high court "lowered itself to the level of common politics" in handing down its decision.

The Southern Manifesto

Indeed resentment to the high court ruling was so bitter that in March 1956 the Congress issued the Southern Manifesto, In many ways, this signal of protest is an astounding and brazen rejection of Constitutional law (as well as the authority of the Supreme Court as its interpreter) by members of Congress.

Moreover, it was signed by 101 politicians (99 Democrats) from Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia.

The Manifesto is a exhibition of the power the Southern Democrats once held before the Civil Rights Era. In all there were 82 Representatives and 19 Senators—roughly one-fifth of the membership of Congress.

(Here's a list of the names who signed the Southern Manifesto.)

All of the states that had once composed the Confederacy signed on to the manifesto. At that time the South- forever reactionary- was ruled by the Southern Democrats who opposed any attempt at civil rights reform as an interference by the North. In making this argument, the Manifesto claims to stand for reserved powers of the states and their sovereign rights.

The policy of separate but equal, the Manifesto states, had "became a part of the life of the people of many of the States"- meaning the Southern states. This doctrine "confirmed their habits, traditions, and way of life."

Furthermore, the Manifesto declared, the segregationist policy was "founded on elemental humanity and common sense, for parents should not be deprived by Government of the right to direct the lives and education of their own children."

That document accused the Supreme Court of judicial activism, and "clear abuse of judicial power" and like Obamacare, abortion and more recently marriage equality, the politicians vowed to use "all lawful means to bring about a reversal of this decision which is contrary to the Constitution and to prevent the use of force in its implementation."

The Manifesto declared also that the ruling was in violation of the states' rights provision of the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The same justification was once used against the abolition of slavery.

(In fact, rarely does the Supreme Court declare laws unconstitutional for violating the Tenth Amendment. This hasn't however stopped groups using it as a basis for challenging high court rulings like gun control, immigration, marijuana laws, and healthcare.).

Virginia Senator Harry Flood Byrd, Sr called for "massive resistance" against the desegregation plan. School integration would be fought by state legislative action, he said. In his state, he proposed, for example, the enactment of state laws eliminating funding — or closing — integrated public schools, and allowing the state to seize and close any school that dares to integrate. He also advocated tax credits to be granted to parents who sent their children to segregated private schools.

Other officials in the South realized that any legal challenge was unwinnable. That didn't mean they weren't prepared to use whatever means possible to stop the desegregation from taking effect. The strategy was simple too.

Alabama Attorney General (and later Governor) John Patterson said

In other words, obstructionism in the face of defeat. It was the kind of political stand that would earn him an endorsement from the KKK." the best thing for us to do would be to never admit that, of course, but to fight a delaying action in the courts. ... delay every way we could do it. ... avoid having a decision made in court, if possible, at all costs, anticipating that the decision would be against us. Now this was our approach. ... so that they'd [Blacks] have to take us on, on a broad front, in a multitude of cases.

White Citizens’ Councils

The reaction to the SCOTUS decision wasn't confined to the state capitols. The public, taking their cues from their state legislators, openly protested the move to implement desegregation plans.

White segregationists of the South established local groups called White Citizens’ Councils (WCC).

According one source, Martin Luther King, in a 1956 New York speech, described the WCC as a modern Ku Klux Klan, targeting black and white people supportive of civil rights.

These groups typically drew a more middle and upper-class membership than the KKK and, in addition to using violence and intimidation to counter civil rights goals, they sought to economically and socially oppress blacks.

Originating in Mississippi, the WCC quickly spreads across the South. Its local councils use economic retaliation such as firings, evictions, and foreclosures, public condemnation, economic boycotts, legislative lobbying, and legal strategems to preserve the "southern way of life." While Blacks are the main focus of council attacks, any whites who accept integration or refuse to retailiate against Blacks are also targeted. As is anyone associated with a trade union regardless of race.

In the latter half of the 1950s, the White Citizens' Councils attempted to indoctrinate a new generation by producing children's books that taught that Heaven is segregated.

By September 1957, emotions had cooled down temporarily. At least, the battle lines were now drawn. Border states had managed to adopt the integration plan without too much problem. However, as the tide of reform reached the Old South, things began to heat up.

A Moment in Charlotte

That year saw all white schools in Charlotte, North Carolina integrating 4 black students with the support of local officials and police. One of those that applied for transfers at a white school was a fifteen-year-old girl named Dorothy Counts.

LIFE Magazine September 16, 1957, carries a pictorial about the state of integration at the moment.

In places both youngsters and their elders greeted the handful of Negros that entered all-white schools with insults, threats and even violence. In reporting this the national press was accused by some Southerners of distorting the school situation. But the photographic testimony was irrefutable.

The photos are indeed hard to look at. You have to wonder what they were thinking as they jeered.

Although the crowd that surrounded Dorothy Counts was small and most of them were likely to be more curious than hostile. it clearly had the tacit approval of the rest of the white population.

If nothing else. the photos provide ample evidence against the idea of majority rule. Allowing referendums to dictate the rights of the minority is a dangerous idea, but we still see the same ideas propagated when it comes, for example, to the issue of same-sex marriage. It only takes a small but loud and intimidating group to the majority against a targeted group.

The troublemakers were a small minority but a dangerous one. Frequently as one report noted, the grownup tormentors were not "people of substance in the community." The cruelest jeers for the Negro students were those that came from their white schoolmates, who drew encouragement from adults. But from the white youngsters also came the first sudden kindnesses.

She told reporters that she could not understand why people did not accept her for who she was.

"I felt that I had the right to be there."

However, after two weeks, the Counts family refuse to endanger their child in the face of such harassment. Who would?

Dot’s parents feared so much for her safety that they pulled her out after just 4 days of attending. Dot’s parents sent her to Philadelphia were the schools were already integrated.

* * *

A half century later, Dot Counts-Scoggins, perhaps surprisingly given the circumstances, still resides in Charlotte. Today it is a different place.

In spite of all the press attention on that opening day, the process of integrating schools and other public facilities went relatively smoothly.

As far as Ms. Counts, she got on with her life.

After high school in Pennsylvania, she returned to Charlotte to attend college at Johnson C. Smith University.

Ms. Counts would go on to earn a degree in psychology and sociology. Until two years ago, she operated a faith-based child care center that served low-income kids.

She was eventually honored with a diploma from Harding High school and in 2010, a building in the school was named after her.

When asked about the effects of the trauma, she reflects:

Though now retired, her former co-workers said of Dorothy"What happened on that day really set me on a path, I've always wanted to work to make sure that bad things don't happen to other children."

"Dot Counts-Scoggins is a true servant leader. She believes that all children should have the opportunity to reach their potential and be amazing."

But does she harbor ill-feeling?

Apparently not. Not only has she forgiven them. She has become friends with the very men in the photos that once upon a time, were so eager to humiliate her.

Apparently not. Not only has she forgiven them. She has become friends with the very men in the photos that once upon a time, were so eager to humiliate her.

What History Teaches

In the end, this part of our not-so-edifying history has a few lessons to teach us. The first of these is that patience matched with unyielding perseverance cannot be overcome by political obstruction and old-fashioned bigotry. They can make life difficult. They can make advancement slower and they can divide the community that need not be divided. But, and here's the important part, they cannot stop progress unless we allow them to.

Unlike many other countries, Americans, rich and poor, the powerful and the weak, have the force of the Constitution on their side. Admittedly, though very often, it seems as though justice is wandering lost in a desert of self-interest, backwardness, and intimidation by the dominant majority. It may be perfect, but it still gives American minorities a fighting chance.

Secondly- and this is something that worries Dot Counts-Scoggins- the advancement of progress can just as easily go retrograde. Progress must be protected and for that, it must be appreciated, respected and revere. If not, we could see America taken back to a darker time.

Lastly, often times, the burden of resistance falls on the shoulders of individuals who have the courage to test the platitudes we say we believe in.

Even when those individuals, like Dorothy Counts, do not succeed directly, history teaches. they will inspire others to follow. Or perhaps they will shame an entire nation.

As she was spit on, shouted at and humiliated by the white crowd, she could have never imagined that one day in her lifetime she would see a black president of the United States.

That's some kind of vindication for four days of torment.